Week 7 [Fri, Feb 23rd] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

While the next few topics are optional, we recommend that you have a quick look anyway, just so that you know their existence at least.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

JavaFX is not required for this course as we strongly discourage you from creating a GUI app. If you are still interest to learn JavaFX, given below is a link to some tutorials.

Javadoc

Guidance for the item(s) below:

You'll need to add JavaDoc comments to the iP code this week. Let's learn how to do that.

Can explain JavaDoc

JavaDoc is a tool for generating API documentation in HTML format from comments in the source code. In addition, modern IDEs use JavaDoc comments to generate explanatory tooltips.

An example method header comment in JavaDoc format:

/**

* Returns an Image object that can then be painted on the screen.

* The url argument must specify an absolute {@link URL}. The name

* argument is a specifier that is relative to the url argument.

* <p>

* This method always returns immediately, whether or not the

* image exists. When this applet attempts to draw the image on

* the screen, the data will be loaded. The graphics primitives

* that draw the image will incrementally paint on the screen.

*

* @param url an absolute URL giving the base location of the image

* @param name the location of the image, relative to the url argument

* @return the image at the specified URL

* @see Image

*/

public Image getImage(URL url, String name) {

try {

return getImage(new URL(url, name));

} catch (MalformedURLException e) {

return null;

}

}

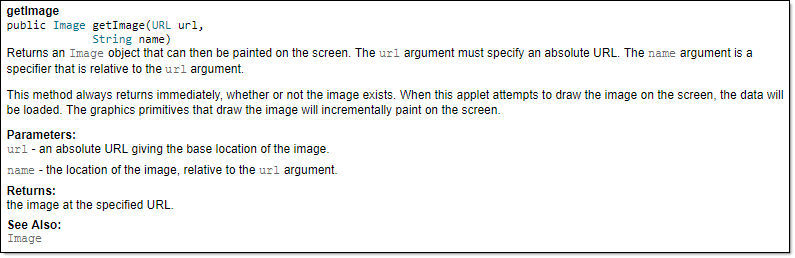

Generated HTML documentation:

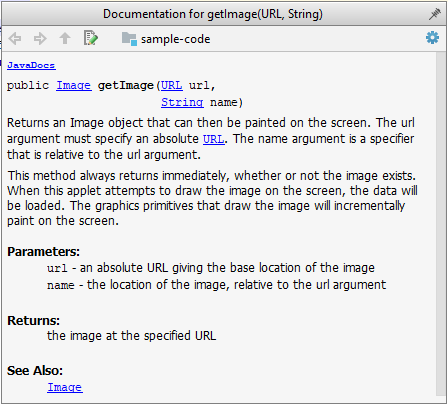

Tooltip generated by IntelliJ IDE:

Can write JavaDoc comments

In the absence of more extensive guidelines (e.g., given in a coding standard adopted by your project), you can follow the two examples below in your code.

A minimal JavaDoc comment example for methods:

/**

* Returns lateral location of the specified position.

* If the position is unset, NaN is returned.

*

* @param x X coordinate of position.

* @param y Y coordinate of position.

* @param zone Zone of position.

* @return Lateral location.

* @throws IllegalArgumentException If zone is <= 0.

*/

public double computeLocation(double x, double y, int zone)

throws IllegalArgumentException {

// ...

}

A minimal JavaDoc comment example for classes:

package ...

import ...

/**

* Represents a location in a 2D space. A <code>Point</code> object corresponds to

* a coordinate represented by two integers e.g., <code>3,6</code>

*/

public class Point {

// ...

}

Resources:

- A short tutorial on writing JavaDoc comments -- from tutorialspoint.com

- A more detailed description -- from Oracle

Guidance for the item(s) below:

This is the final installment of the code quality topics. As you are learning about JavaDoc comments this week, you can also learn these guidelines to write better code comments.

Can explain the need for commenting minimally but sufficiently

Good code is its own best documentation. As you’re about to add a comment, ask yourself, ‘How can I improve the code so that this comment isn’t needed?’ Improve the code and then document it to make it even clearer. -- Steve McConnell, Author of Clean Code

Some think commenting heavily increases the 'code quality'. That is not so. Avoid writing comments to explain bad code. Improve the code to make it self-explanatory.

Can improve code quality using technique: do not repeat the obvious

Do not repeat in comments information that is already obvious from the code. If the code is self-explanatory, a comment may not be needed.

Bad

//increment x

x++;

//trim the input

trimInput();

Bad

# increment x

x = x + 1

# trim the input

trim_input()

Can improve code quality using technique: write to the reader

Write comments targeting other programmers reading the code. Do not write comments as if they are private notes to yourself. Instead, One type of comment that is almost always useful is the header comment that you write for a class or an operation to explain its purpose.

Bad Reason: this comment will only make sense to the person who wrote it

// a quick trim function used to fix bug I detected overnight

void trimInput() {

....

}

Good

/** Trims the input of leading and trailing spaces */

void trimInput() {

....

}

Bad Reason: this comment will only make sense to the person who wrote it

def trim_input():

"""a quick trim function used to fix bug I detected overnight"""

...

Good

def trim_input():

"""Trim the input of leading and trailing spaces"""

...

Can improve code quality using technique: explain what and why, not how

Comments should explain the WHAT and WHY aspects of the code, rather than the HOW aspect.

WHAT: The specification of what the code is supposed to do. The reader can compare such comments to the implementation to verify if the implementation is correct.

Example: This method is possibly buggy because the implementation does not seem to match the comment. In this case, the comment could help the reader to detect the bug.

/** Removes all spaces from the {@code input} */

void compact(String input) {

input.trim();

}

WHY: The rationale for the current implementation.

Example: Without this comment, the reader will not know the reason for calling this method.

// Remove spaces to comply with IE23.5 formatting rules

compact(input);

HOW: The explanation for how the code works. This should already be apparent from the code, if the code is self-explanatory. Adding comments to explain the same thing is redundant.

Example:

Bad Reason: Comment explains how the code works.

// return true if both left end and right end are correct

// or the size has not incremented

return (left && right) || (input.size() == size);

Good Reason: The code is now self-explanatory -- the comment is no longer needed.

boolean isSameSize = (input.size() == size);

return (isLeftEndCorrect && isRightEndCorrect) || isSameSize;

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Modern software projects, and your tP, make heavy use of build/CI/CD tools The topics below give you an overview of those tools, to prepare you to start using them yourself.

Can explain build automation tools

Build automation tools automate the steps of the build process, usually by means of build scripts.

In a non-trivial project, building a product from its source code can be a complex multi-step process. For example, it can include steps such as: pull code from the revision control system, compile, link, run automated tests, automatically update release documents (e.g. build number), package into a distributable, push to repo, deploy to a server, delete temporary files created during building/testing, email developers of the new build, and so on. Furthermore, this build process can be done ‘on demand’, it can be scheduled (e.g. every day at midnight) or it can be triggered by various events (e.g. triggered by a code push to the revision control system).

Some of these build steps such as compiling, linking and packaging, are already automated in most modern IDEs. For example, several steps happen automatically when the ‘build’ button of the IDE is clicked. Some IDEs even allow customization of this build process to some extent.

However, most big projects use specialized build tools to automate complex build processes.

Some popular build tools relevant to Java developers: Gradle, Maven, Apache Ant, GNU Make

Some other build tools: Grunt (JavaScript), Rake (Ruby)

Some build tools also serve as dependency management tools. Modern software projects often depend on third party libraries that evolve constantly. That means developers need to download the correct version of the required libraries and update them regularly. Therefore, dependency management is an important part of build automation. Dependency management tools can automate that aspect of a project.

Maven and Gradle, in addition to managing the build process, can play the role of dependency management tools too.

Can explain continuous integration and continuous deployment

An extreme application of build automation is called continuous integration (CI) in which integration, building, and testing happens automatically after each code change.

A natural extension of CI is Continuous Deployment (CD) where the changes are not only integrated continuously, but also deployed to end-users at the same time.

Some examples of CI/CD tools: Travis, Jenkins, Appveyor, CircleCI, GitHub Actions

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Let's learn how to merge a PR on GitHub; you need to do that in the tP later, and you'll be practicing PR merging in the iP this week.

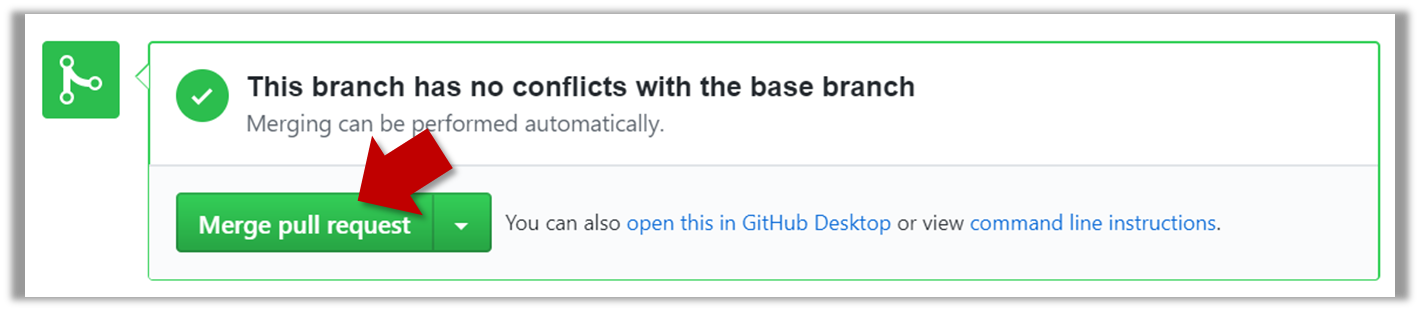

Can review and merge PRs on GitHub

Let's look at the steps involved in merging a PR, assuming the PR has been reviewed, refined, and approved for merging already.

Preparation: If you would like to try merging a PR yourself, you can create a dummy PR in the following manner.

- Fork any repo (e.g., samplerepo-pr-practice).

- Clone in to your computer.

- Create a new branch e.g., (

feature1) and add some commits to it. - Push the new branch to the fork.

- Create a PR from that branch to the

masterbranch in your fork. Yes, it is possible to create a PR within the same repo.

1. Locate the PR to be merged in your repo's GitHub page.

2. Click on the Conversation tab and scroll to the bottom. You'll see a panel containing the PR status summary.

3. If the PR is not merge-able in the current state, the Merge pull request will not be green. Here are the possible reasons and remedies:

- Problem: The PR code is out-of-date, indicated by the message This branch is out-of-date with the base branch. That means the repo's

masterbranch has been updated since the PR code was last updated.- If the PR author has allowed you to update the PR and you have sufficient permissions, GitHub will allow you to update the PR simply by clicking the Update branch on the right side of the 'out-of-date' error message. If that option is not available, post a message in the PR requesting the PR author to update the PR.

- Problem: There are merge conflicts, indicated by the message This branch has conflicts that must be resolved. That means the repo's

masterbranch has been updated since the PR code was last updated, in a way that the PR code conflicts with the currentmasterbranch. Those conflicts must be resolved before the PR can be merged.- If the conflicts are simple, GitHub might allow you to resolve them using the Web interface.

- If that option is not available, post a message in the PR requesting the PR author to update the PR.

3. Merge the PR by clicking on the Merge pull request button, followed by the Confirm merge button. You should see a Pull request successfully merged and closed message after the PR is merged.

- You can choose between three merging options by clicking on the down-arrow in the Merge pull request button. If you are new to Git and GitHub, the

Create merge commitoptions are recommended.

Next, sync your local repos (and forks). Merging a PR simply merges the code in the upstream remote repository in which it was merged. The PR author (and other members of the repo) needs to pull the merged code from the upstream repo to their local repos and push the new code to their respective forks to sync the fork with the upstream repo.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next, you will learn a workflow called the 'Forking Flow', which combines the various Git and GitHub techniques you have been learning over the past few weeks. It is also the workflow you will use in the tP.

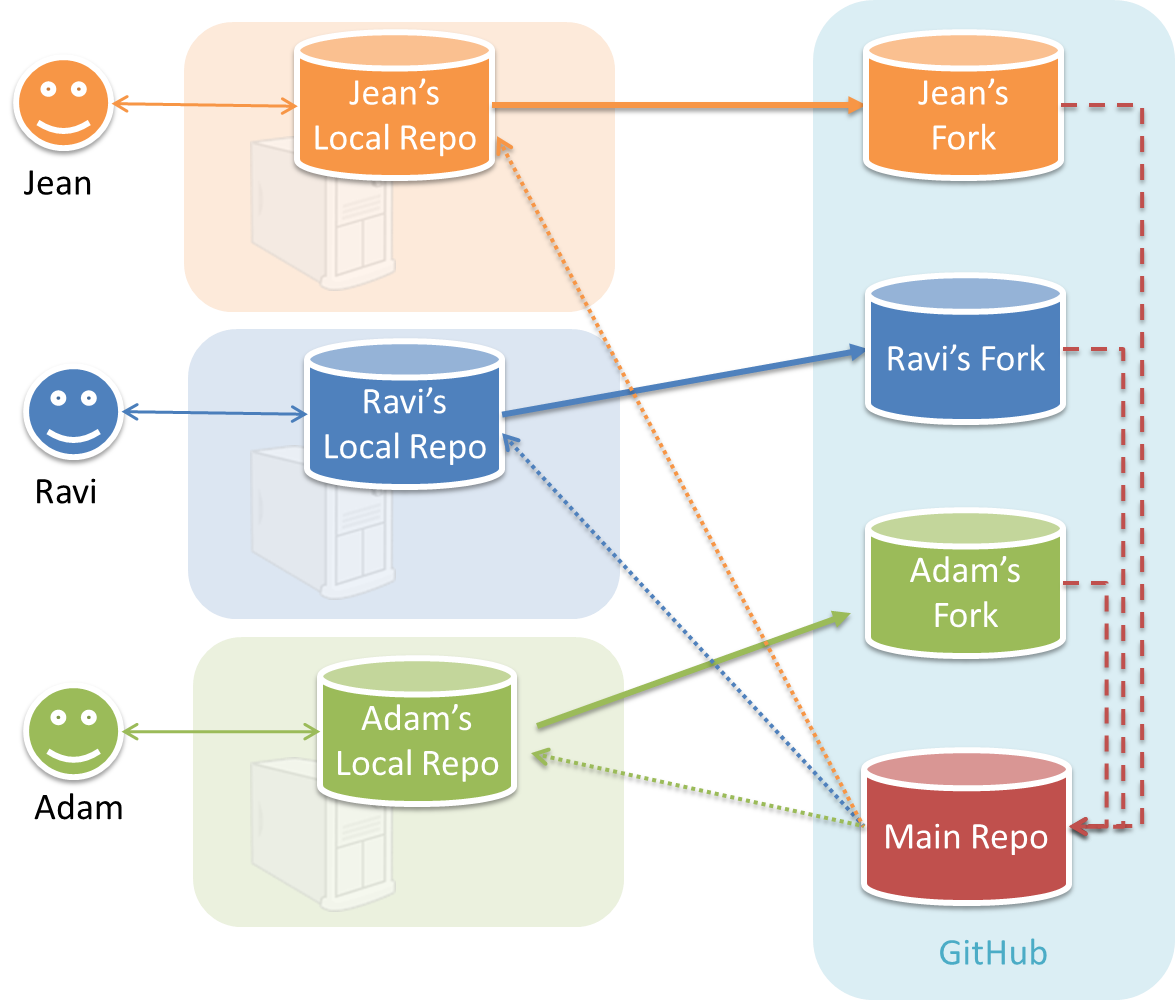

Can explain forking workflow

In the forking workflow, the 'official' version of the software is kept in a remote repo designated as the 'main repo'. All team members fork the main repo and create pull requests from their fork to the main repo.

To illustrate how the workflow goes, let’s assume Jean wants to fix a bug in the code. Here are the steps:

- Jean creates a separate branch in her local repo and fixes the bug in that branch.

Common mistake: Doing the proposed changes in themasterbranch -- if Jean does that, she will not be able to have more than one PR open at any time because any changes to themasterbranch will be reflected in all open PRs. - Jean pushes the branch to her fork.

- Jean creates a pull request from that branch in her fork to the main repo.

- Other members review Jean’s pull request.

- If reviewers suggested any changes, Jean updates the PR accordingly.

- When reviewers are satisfied with the PR, one of the members (usually the team lead or a designated 'maintainer' of the main repo) merges the PR, which brings Jean’s code to the main repo.

- Other members, realizing there is new code in the upstream repo, sync their forks with the new upstream repo (i.e. the main repo). This is done by pulling the new code to their own local repo and pushing the updated code to their own fork. If there are unmerged branches in the local repo, they can be updated too e.g., by merging the new

masterbranch to each of them.

Possible mistake: Creating another 'reverse' PR from the team repo to the team member's fork to sync the member's fork with the merged code. PRs are meant to go from downstream repos to upstream repos, not in the other direction.

One main benefit of this workflow is that it does not require most contributors to have write permissions to the main repository. Only those who are merging PRs need write permissions. The main drawback of this workflow is the extra overhead of sending everything through forks.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

The activity in the section below can be skipped as you will be doing a similar activity in a coming tutorial.

Can follow Forking Workflow

You can follow the steps in the simulation of a forking workflow given below to learn how to follow such a workflow.

This activity is best done as a team.

Step 1. One member: set up the team org and the team repo.

Create a GitHub organization for your team, if you don't have one already. The org name is up to you. We'll refer to this organization as team org from now on.

Add a team called

developersto your team org.Add team members to the

developersteam.Fork se-edu/samplerepo-workflow-practice to your team org. We'll refer to this as the team repo.

Add the forked repo to the

developersteam. Give write access.

Step 2. Each team member: create PRs via own fork.

Fork that repo from your team org to your own GitHub account.

Create a branch named

add-{your name}-info(e.g.add-johnTan-info) in the local repo.Add a file

yourName.mdinto themembersdirectory (e.g.,members/jonhTan.md) containing some info about you into that branch.Push that branch to your fork.

Create a PR from that branch to the

masterbranch of the team repo.

Step 3. For each PR: review, update, and merge.

[A team member (not the PR author)] Review the PR by adding comments (can be just dummy comments).

[PR author] Update the PR by pushing more commits to it, to simulate updating the PR based on review comments.

[Another team member] Approve and merge the PR using the GitHub interface.

[All members] Sync your local repo (and your fork) with upstream repo. In this case, your upstream repo is the repo in your team org.

- The basic mechanism for this has two steps (which you can do using Git CLI or any Git GUI):

(1) First, pull from the upstream repo -- this will update your clone with the latest code from the upstream repo.

If there are any unmerged branches in your local repo, you can update them too e.g., you can merge the new master branch to each of them.

(2) Then, push the updated branches to your fork. This will also update any PRs from your fork to the upstream repo. - Some alternatives mechanisms to achieve the same can be found in this GitHub help page.

If you are new to Git, we recommend that you use the above two-step mechanism instead, so that you get a better view of what's actually happening behind the scene.

- The basic mechanism for this has two steps (which you can do using Git CLI or any Git GUI):

Step 4. Create conflicting PRs.

[One member]: Update README: In the

masterbranch, remove John Doe and Jane Doe from theREADME.md, commit, and push to the main repo.[Each team member] Create a PR to add yourself under the

Team Memberssection in theREADME.md. Use a new branch for the PR e.g.,add-johnTan-name.

Step 5. Merge conflicting PRs one at a time. Before merging a PR, you’ll have to resolve conflicts.

[Optional] A member can inform the PR author (by posting a comment) that there is a conflict in the PR.

[PR author] Resolve the conflict locally:

- Pull the

masterbranch from the repo in your team org. - Merge the pulled

masterbranch to your PR branch. - Resolve the merge conflict that crops up during the merge.

- Push the updated PR branch to your fork.

- Pull the

[Another member or the PR author]: Merge the de-conflicted PR: When GitHub does not indicate a conflict anymore, you can go ahead and merge the PR.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Git is considered a DRCS. Read the topic below to learn what that means and how it differs from the alternative.

Can explain DRCS vs CRCS

RCS can be done in two ways: the centralized way and the distributed way.

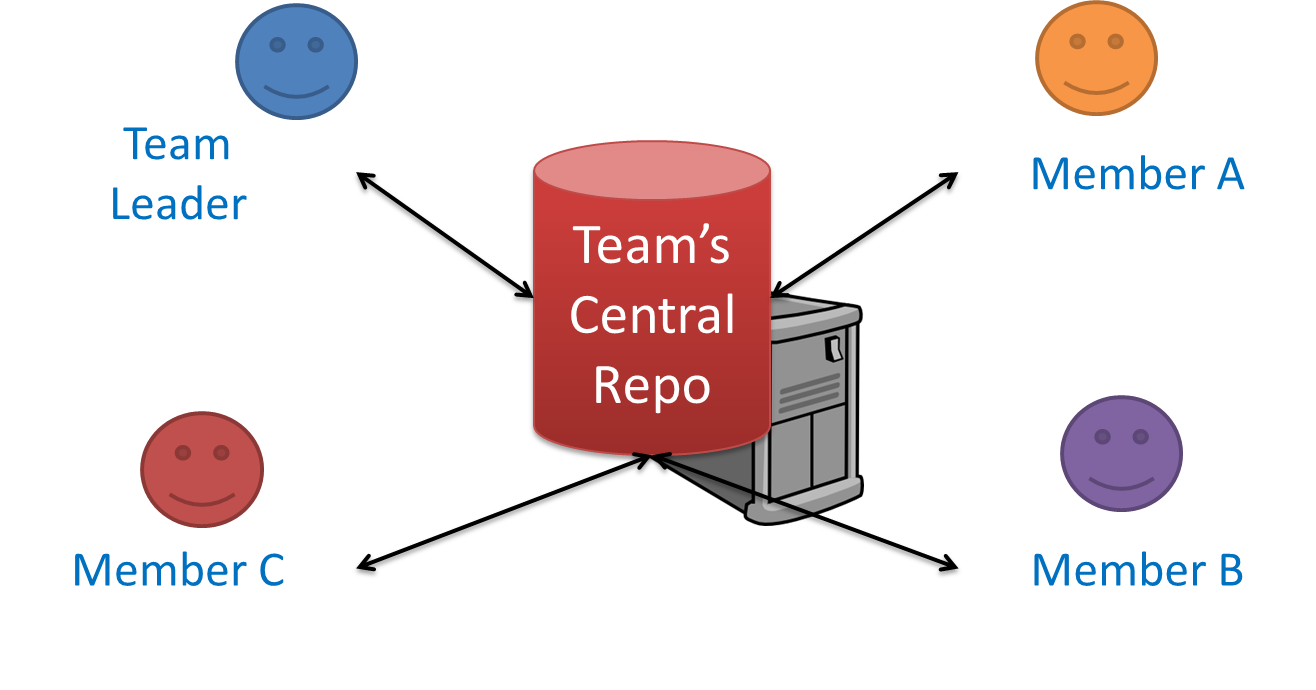

Centralized RCS (CRCS for short) uses a central remote repo that is shared by the team. Team members download (‘pull’) and upload (‘push’) changes between their own local repositories and the central repository. Older RCS tools such as CVS and SVN support only this model. Note that these older RCS do not support the notion of a local repo either. Instead, they force users to do all the versioning with the remote repo.

The centralized RCS approach without any local repos (e.g., CVS, SVN)

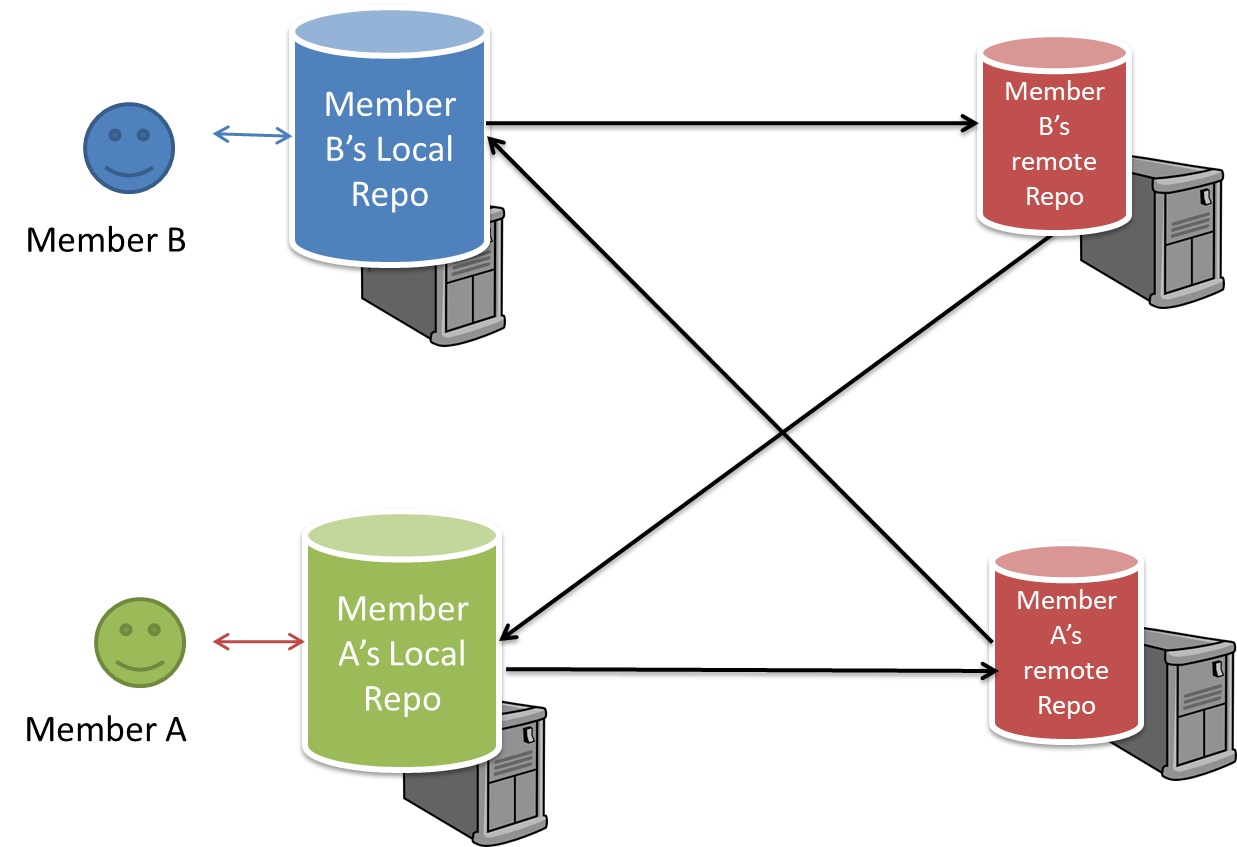

Distributed RCS (DRCS for short, also known as Decentralized RCS) allows multiple remote repos and pulling and pushing can be done among them in arbitrary ways. The workflow can vary differently from team to team. For example, every team member can have his/her own remote repository in addition to their own local repository, as shown in the diagram below. Git and Mercurial are some prominent RCS tools that support the distributed approach.

The decentralized RCS approach

Guidance for the item(s) below:

These are two workflows that are riskier (but simpler) than the forking flow. After following the forking flow for a while, you may switch to one of these, but at your own risk.